Electronic

Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences

Guelph School of Japanese Sword Arts, July, 2005

Kata and Etudes: Pattern Drills in the History of Teaching

Swordsmanship

Charles Ham

Abstract

Teaching methods for the use of hand weapons during

the19th century were remarkably similar in both Europe and Japan.

This paper analyzes Hungarian and Highland Broadsword and its companion

publication The Manual of the Ten Divisions of the Highland Broadsword

by Maestro Harry Angelo (1799 and 1800, respectively) and that system’s

antecedents in the cutlass training of English speaking navies, and the

exercise known as Tachi Uchi no Kurai from the Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu

(MJER) and Muso Shinden Ryu (MSR) schools of Japanese

swordsmanship. The training methods from both the Highland

broadsword/cutlass tradition and the Japanese tradition have several

common elements; chiefly that a more experienced swordsman leads a

partner through a series of hypothetical swordfights. These

hypothetical swordfights are then memorized and practiced until the

responses become automatic. These extended drills, called

“lessons,” “divisions” or “etudes” (Fr. "lesson") in early 19th century

English and “kata” in Japanese, formed the foundation of

training.

However, the etudes are fundamentally different from

kata in one significant way. In the Highland broadsword/cutlass

tradition the basic strategy stayed the same, but the lessons were

rewritten by the next generation of maestros who often dropped them in

favor of drills and free sparing. This can be seen by looking at the

manuals and drill books of successive maestros. By looking at how

the two sister schools, MSR and MJER, have very different

interpretations of their kata in the late 20th century, one can see

that the Japanese kata are kept more or less intact, but evolve due to

differences of interpretation by various maestro over the years.

The author poses a hypothesis that this difference in how the skills

are transmitted through the generations is a reflection of the unique

values of the two cultures.

On a personal note

Four years ago I started trading Muso Shinden Ryu Iaido lessons for

saber lessons with a local fencing coach. One day he brought in a

set of singlesticks and said that this is actually what the militaries

used in the nineteenth century to teach the use of the cutlass and the

saber. That caught my attention, and I was hooked on the new

method and equipment.

After doing some research I found the singlestick had a long and

twisted history including being part of Olympic fencing 100 years

ago. It was a prize fighting weapon 200 years ago and was also

used as a training tool for the Scottish Highland’s Basket-hilted

broadsword. By the late 19th and early 20th century the

singlestick was used most often by navies to teach cutlass skills and

was considered by most people to be the training tool for the cutlass,

the same way the foil was the training tool for the court sword.

I downloaded drill books from the Internet and joined online groups

centered on singlestick and historical basket-hilted broadsword

groups. The groups that I joined were trying to revive

singlestick, but two years after starting singlestick it turned out

that there were two isolated groups in Great Britain that had been

doing singlestick fencing continuously even after the weapon was

dropped from Olympic fencing. There are therefore unbroken lines

of teaching in this tradition.

One group I joined, The Cateran Society, is interested in the roots of

the Highland Broadsword lessons of Harry Angelo. Angelo

collaborated with an artist named Rowlandson to publish a beautifully

illustrated manual and a poster on the subject in 1799 and in 1801 and

introduced the singlestick as the safety weapon for this style of

swordsmanship. Fifteen years later Angelo was hired to teach

cutlass to Royal Naval shipmen and he used his Highland broadsword

system for cutlass as well.

The Cateran Society was excited by the fact that their reconstruction

of British Highland Regimental Broadsword skills was very similar to

the living remnant of singlestick and took this as proof that their

method of reconstruction was valid (1). I would agree with them

on this point, but what fascinated me were the differences between what

the Cateran Society and the remnant groups of singlestick fencers were

doing. One thing different was the Cateran Society’s training

methods revolved around learning etudes. The Cateran Society was

doing the etudes from Angelo’s poster, called “Divisions” by Angelo, or

“Lessons” by the members of the Cateran Society. These etudes

struck me as being very similar to kata from Japanese sword arts.

However, the remnant groups, as far as I have been able to find out, do

not use etudes in their training.

Etudes and kata:

There are two points this paper will explore. The first will show

that kata from the Japanese sword arts tradition, and etudes from the

late 18th early 19th century in European fencing are essentially the

same thing by another name. The second point I want to explore is

the method of transmission. The Japanese kata tend to evolve,

while each generation of fencing masters wrote their own etudes, which

by mid century were reduced to simpler response drills. The

difference in transmission in these two traditions points to

differences in the attitudes of the base culture of each tradition

toward the art of the sword.

Tachi Uchi no Kurai

In the Tachi Uchi no Kurai two people with wood swords go through a

series of less than a dozen short mock sword fights (2). One

person, the Shidachi, is the student who plays the part of the winner,

and the other, the Uchidachi, the more senior person, plays the

looser. The mock fights show combinations, have different types

of initiative (sen in Japanese) and serve as examples of

strategy.

The Tachi Uchi no Kurai, like kata in many Japanese sword arts, is

supposed to be memorized and drilled until it is automatic. The

purpose of kata in all Japanese sword arts is to teach swordsmanship

and kata are similar to drills in that the purpose is to have the

correct actions put into the student’s motor memory.

Pedagogically speaking, the kata are basically two-person combination

drills. However, looking at Tachi Uchi no Kurai in more detail,

the various sections teach more than combinations of attacks.

They also teach defense and give more than one option for similar

situations. Sections often have sister sections that start out

the same, but the opponent, played by the senior, has different

responses to the student’s strategy.

Compare the first kata, Deai to the second one, Tsukekomi. Both

start with the opponents advancing toward one another with weapons

sheathed. The senior partner (Uchidachi) draws and cuts at the

student’s (Shidachi’s) thigh with a one handed cut. The student

draws simultaneously and blocks the cut with a one-handed edge-to-edge

parry that looks very similar to the cut. From there, however,

the two kata diverge. In Deai, the senior breaks contact with the

student’s sword and the student attacks the senior’s head with a two

handed downward cut which the senior blocks just in the nick of time

with a two handed cross block. In Tsukekomi, the senior keeps

pressure on the students blade so the student is forced to do a

different counter. While maintaining contact with the opponent’s

sword the student steps forward left and grabs the senior’s sword hand

with the student’s left hand. Now with control of the opponent’s

sword, the student stabs the opponent in the side.

Kata three, Ukenagashi, and kata four, Ukekomi, also start out

similarly, with two diagonal cuts across the body which are met with

edge on edge parries. In both the student keeps distance and

maintains good defense while looking for an opening. The senior,

seeing no immediate opening, steps back into jodan no kamae, a ready

stance with the sword held above the head, ready to strike

downward.

When Uchidachi steps back into jodan no kamae the student has two

options: In kata three, Ukenagashi, the student goads the senior into

cutting straight down by going to gedan, a stance with the tip of the

sword lowered (3). When the senior cuts down the student brings

the sword up to parry the opponent’s blade and uses the momentum of the

connection to swing the sword around and cut the opponent at the

neck/shoulder junction. In kata four, Ukekomi, the student uses a

different technique that is even more difficult. The student

follows the opponent as he steps back and cuts with a rising cut as the

opponent lifts his own sword into jodan. Before the opponent has

even arrived into jodan to assess the situation the student has cut him

across the chest.

The Tachi Uchi no Kurai are very carefully planned. The student

learns to neutralize common attacks and is given a couple of variations

on how the opponent may respond to counters. Since combinations

are emphasized, one can see the strategy of MSR and MJER.

Strategy is not explicitly taught, but by internalizing the kata one

should ideally start to use it even in stress situations. Kata,

therefore, are not just combination drills or response drills but are

also a curriculum and a syllabus for the school’s deeper

strategy.

Angelo’s Ten Divisions

One sees parallels in Angelo’s Ten Divisions. First, two people

armed with singlesticks, a wooden substitute for the basket-hilted

sword, engage in ten short mock sword fights. The less senior

soldier plays the defender and is led through the etudes by the more

senior soldier as antagonist. To go deeper we must examine

Angelo’s poster more carefully, but the poster, like scrolls from

traditional Japanese martial arts, was a memory aid for the student who

was being taught by the regiment’s senior soldiers and therefore has

some gaps (e.g. beginning guard positions and transitional

movements). The textbook used by the Cateran Society (Thompson,

2001) has filled in those gaps by referring to contemporary authors who

also wrote manuals on Highland Swordsmanship but did not have official

governmental sanction like Angelo (4). However, the detailed

illustrations clearly show the progression of two soldiers going

through the Ten Divisions. The basic strategy of each exercise is clear

even though some details are lacking.

Angelo's mock fights show combinations, feinting, secondary intentions

(attacking one target with the intent to move the opponent to expose

another target) and strategy. The various sections teach

effective combinations and often have pairs of divisions that start out

the same but have different responses by the senior partner or have

variations on the combination.

The first three divisions start out the same and build on one

another. They introduce a fundamental aspect of Highland

swordsmanship – an attack to the head and then an attack to the leg

(Thompson 2001: 92). This system puts heavy emphasis on keeping

distance and defense, therefore the student steps back with the lead

foot (traversing) with each parry.

In the first division, the student attacks the head which is parried

and has to parry the senior soldier’s counterattack. As soon as

the counterattack is dealt with the student cuts for the lead leg of

his opponent. The senior soldier steps out of range of the leg

attack and this division ends in a draw.

The second division starts out like the first one with the student

making an attack to the head followed by an attack to the opponent's

lead leg, but the student is introduced to a new concept: he does not

traverse with the parry just before the leg attack to gain some

distance. So the student parries an attack from the senior

soldier without traversing (bringing the lead leg back behind the

trailing leg) and once again attacks the leg. The senior manages

to avoid the second leg attack by traversing the target out of range

(i.e. moves the right leg behind the left leg). The second

division also ends in a draw. The third division is the same as

the second division, but the second leg attack is extended to include a

cut to the opponent’s ribs.

Divisions seven and ten are both circular; they both teach an effective

combination by having the student do that combination then have the

opponent attack with the same combination so the student is forced to

learn the counter. In division seven, the student attacks the

head to force the opponent into a cross guard (sword held above the

head more or less horizontal to block downward blows directed at the

head) and then the student attacks the exposed arm and side of the

head. The opponent manages to just parry with an inside guard and

then the opponent counters with the same combination of attacks.

The student tries another combination of head and ribs which is then

followed by the opponent parrying with a hanging guard and countering

with the same combination. While division ten has different

combinations, it follows the same pattern of having the student do two

effective combinations and the defenses against each.

Angelo has also very carefully planned out his etudes. Common

attacks and defenses are taught and students learn a couple of

variations on how the opponent may respond. Like Tachi Uchi no

Kurai, combinations are emphasized so one can see the strategy of his

system. Angelo however, did not just rely on the etudes to impart

the techniques. In addition, he published a manual, Hungarian and

Highland Broadsword, In it, he has plates showing explicitly one

aspect of his strategy – to not parry attacks to the lead leg, but

instead to move the leg out of range. This leaves the sword

available for quick counter attacks (Plates 16 and 17).

Comparing Tachi Uchi no Kurai and

Angelo’s Ten Divisions

The evidence shows that late 18th and 19th century etudes and 18th

century kata are essentially the same training method under two

different names. To summarize, the two sets have a similar

structure (less than a dozen short paired encounters) and the same

content (combinations and counters to common attacks). Both have

sections that build on previous sections with variations in the

opponent’s response, both have the same expectations (that students

memorize the fictional encounters) and both have the same motivation

(that these drills will allow the student to use combinations and

strategy in stress encounters). The only structural difference

between the kata and the etudes is that in the kata the student wins

decisively and has to pull the cut in order to not injure the senior

partner. In the etudes the opponent manages to parry the final

cut from the student so the encounter ends in a draw. I propose

that this difference is just a reflection of two different safety

methods the two systems devised.

Method of Transmission

To borrow a metaphor from University of Georgia historian Karl Friday,

the underlying principles and strategies of a Japanese martial art

tradition are like the flame or the light of the lamp, while the kata

is the lamp itself (Friday, 2003: n.p.) (5). Japanese traditional

arts, be they the tea ceremony or the martial arts, use kata to teach,

and the memorization and correct performance of the kata is a necessary

part of advancing in rank. These educational systems try very

hard to pass on both the lamp and the light unchanged. If the

lamp can be passed on unchanged then there is hope that the flame is

the same.

I hypothesize that members of a traditional Japanese martial arts

school see themselves as mastering an art form that has an idealized

perfect form they are striving towards but may never realize. Not

unlike professional ballet dancers who do their basic moves at the

barre every morning, they see themselves as pursuing an unchanging

ideal and so practice the kata in a similar manner. Therefore,

there are really only two ways that kata can be changed. The

first way is when changes to kata are made by people at the highest

level, like menkyo kaiden level (license of complete transmission) or

soke (the owner of the school) to insure that the kata continues to

teach the underlying principles and strategies of the ryuha.

These changes to the lamp are merely repairs to it to insure it

continues to hold the flame. The second type would be the

unconscious change in small details made as the kata are

transmitted. Any such changes to a set of kata would be small,

but over time these could add up to create very different

interpretations. In order to preserve the tradition, changes in

kata should therefore be evolutionary in nature, not

revolutionary.

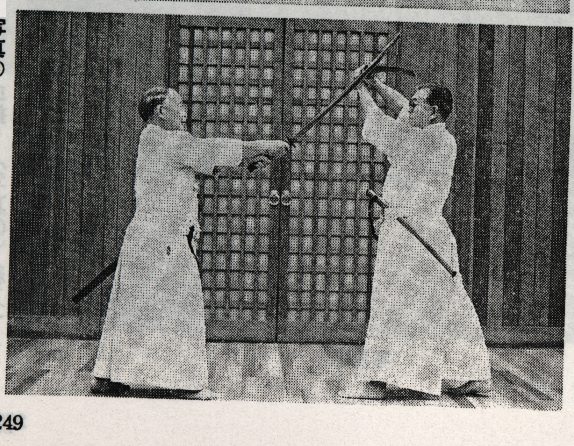

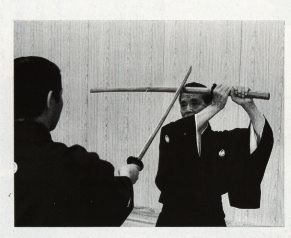

Fig 1 Danzaki

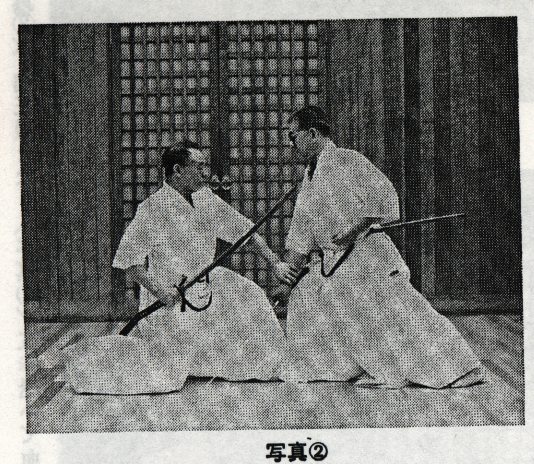

Fig 2 Mitani

Looking again at Tachi Uchi no Kurai, one can see the various

differences that exist between the MSR and the MJER that suggest

evolutionary changes have been at work. With the first kata,

Deai, both Muso Shinden Ryu and Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu have a similar

basic structure, but the final cross block by the senior has

considerable variation. In Muso Shinden Ryu the hilt is

held to the right of the body (Danzaki, 1988: 249), but in Muso Jikiden

Eishin Ryu the cross block is done with the hilt held to the left

side of the body (Mitani, 1986: 129) (see Figures 1 and 2). The

second kata, Tsukekomi, shows an even more important variation in that

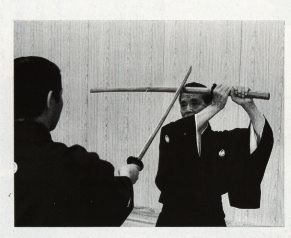

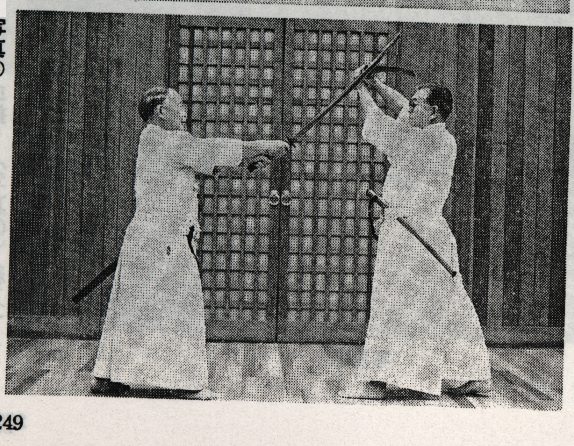

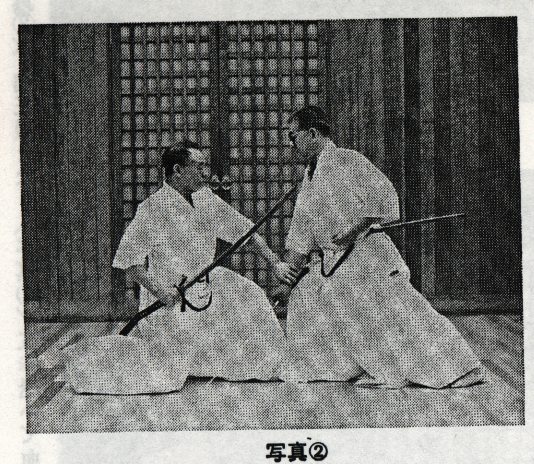

it is the student who does different actions not the senior

partner. As explained above Tsukekomi starts the same as Deai but

has a different ending. The student grabs the opponent’s right

hand which is holding a sword and the student simultaneously steps in

with the left leg. The student then stabs the opponent. The

differences between the two schools are essentially how far to step in

with the left leg. In Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu the student

steps in so deeply that the left knee is forced into the back of the

senior partner’s right knee and the senior partner’s right hand is

brought across the body and pinned against the student’s hip(Mitani,

1986: 133). However, in Muso Shinden Ryu, the student does not

step in so deep, just far enough to allow the stab but prevent getting

entangled with the opponent’s body (Danzaki, 1988: 251) (see Figures 3

and 4).

Fig 3 Mitani

Fig 4 Danzaki

The Highland Broadsword/cutlass tradition shows a very different

attitude toward the transmission of knowledge. Unlike the lamp

and flame metaphor of traditional Japanese education, fishing is a

better metaphor. The underlying principles and strategies are the

important part of the education. The etudes are just a tool to

acquire the knowledge; like a fish hook, the etudes can be discarded

once the prize (the skill or the knowledge or the fish) is in one's

grasp. By reading the fencing literature of the 19th and early

20th century one sees why this is: the masters of Western martial arts

see themselves as engaged in the science of defense and are actively

trying to find the best techniques and strategies as well as the best

teaching methods. Because of this attitude, changes tend to be

quite radical when new "scientific" evidence is introduced. The

changes in this tradition are therefore revolutionary, not

evolutionary.

Soon after the publication of his manual and poster, Angelo began to

occasionally teach navy seamen with the same methods. With

Maestro Angelo’s appointment as Naval Instructor in the Cutlass in

1813, the Ten Divisions were made official part of the British Royal

Navy’s training. This style of swordsmanship was later adopted by

the other English speaking navy, the U.S. Navy. Looking at the

Royal Navy’s cutlass manual of 1873 (McGrath and Barton, 2002) and the

U.S. Navy's cutlass manual of 1904 (Fullam, 1904) one can clearly see

that they are inspired by Angelo. In fact, Plate 153 from Petty

Officer’s Drillbook USN (1904) is almost identical to the etching

entitled “The Advantage of Shifting the Leg” from Hungarian and

Highland Broadsword by Angelo.

However, both of these later manuals have dropped etudes from their

curricula. Both have solo drills of the basic attacks and parries

followed by instructions for partner training where two ranks of men

take turns being attacker and defender. The whole idea of a

senior partner has been done away with – the petty officer or officer

drilling the seamen is the expert while the partners are theoretically

of equal skill. The combination drills that do remain are not

sequentially ordered to build on each other nor do they have

variations. Feinting and secondary intentions are also not

evident in either training manual. The emphasis of both these

manuals is on getting the men ready to free spar, or as it was known at

the time, “loose play.” Instructions for running such practice

between the men occupies a large portion of both manuals. Free

sparing, or loose play was not unknown in the days of Angelo but

comments on it are missing from both his poster and manual. This

is a revolutionary change in the training process, no doubt brought on

by the view that it was more scientific.

The two manuals differ greatly in another aspect that shows

revolutionary change: the guards. The word "guards" in Angelo’s

time meant both the ready positions from which the soldier/sailor

waited for openings and for threats (called kamae in Japanese martial

arts) but also referred to parries. Angelo’s manual has seven

guards but both navies have greatly reduced that number.

Interestingly enough, the U.S. Navy has eliminated the hanging guard

while the Royal Navy continued to place great emphasis on it.

Comparing Methods of Transmission

The ways the two traditions transmitted their skills in the late 19th

and early 20th century are clearly different. The Japanese

preserved their kata and transmitted it with small changes creeping in

over the years. Their evolutionary changes can be observed by

looking at the differences that exist in the two schools' present

interpretations of the kata. This supports the hypothesis that

practitioners of the Japanese sword arts generally see themselves as

pursuing an idealized form of art. To them, seeing very little

change was reassuring evidence that the style was not only true to its

roots but the ideal it represented was a good one. The Highland

Broadsword/cutlass traditions saw themselves as engaged in a

science. They too were pursuing an idealized form, but not an art

form. For them change was a symbol of progress.

We can see that, for at least a short time in the late 18th and early

19th centuries and most likely longer, on two different islands off two

different continents the methods of teaching swordsmanship were

essentially the same. The Japanese have managed to more or less

preserve this old way of teaching because several koryu, old schools,

of swordsmanship have survived and still maintain the kata in unbroken

lines of transmission. The Western world long ago gave up using

etudes to teach swordsmanship and this very fact speaks volumes of how

the practitioners saw themselves and their tradition of

swordsmanship.

However, this paper brings up many questions that the author hopes will

be addressed by other scholars. First of all, in the realm of

anthropology: How do people in various martial arts communities view

change? How do they see themselves fitting into the tradition of

their martial art? In the realm of pedagogy: How effective and

efficient were kata/etudes for training fighting men? Etudes were

dropped by the West in the 19th century when swords were no longer

being used on the battle field and only rarely on the field of honor,

so evidence suggests that they did have at least some effectiveness in

teaching prior to that time. If etudes are an effective teaching

method, why are they effective?

Furthermore, there are also many other similarities in form between

Angelo’s etudes and Tachi Uchi no Kurai. Both Angelo’s set of

etudes and the kata of Tachi Uchi no Kurai have attacks to the leg

defended by counterattacks to the head, edge parries and many other

stylistic parallels. Of course human anatomy and physics is

constant between Japan and Great Britain so one expects some parallels

but the parallels are stronger than one would expect. I look

forward to seeing more research on the parallels in swordsmanship

between Japan and the West.

Acknowledgements

As a novice to the European traditions of the arts of defense I often

depended on the knowledge of others. While they are too numerous

to thank individually in this limited space, I would like to say that

the maestros and scholars in this field who answered my numerous

requests for information were unanimously kind and generous with their

knowledge and time. I hope to have the opportunity to meet my

generous pen-pals someday in a dojo, salle, salon, or taigh suntais

soon.

End Notes

1. For The Cateran Society’s curriculum please see Thompson, 2001.

2. The number of kata in Tachi Uchi no Kurai varies within this

tradition from seven to twelve. I consider it likely that these

kata were done in the 19th century with bokuto (wooden swords).

There are photos of Nakayama Hakudo (a.k.a. Hiromichi, the last

Headmaster of MSR) and his son and photos of Nakayama Hakudo’s

protégé Danzaki and an unidentified partner doing these

kata with actual swords. However, it is most likely that Tachi

Uchi no Kurai was practiced at the end of the 19th century with bokuto

since kata in the 19th century were commonly performed with bokuto by

the vast majority of Japanese schools of defense. Furthermore

many traditions in Japan currently use wooden weapons for training and

use real or at least realistic-looking weapons for

demonstrations.

3. There are several variations in Tachi Uchi no Kurai between the Muso

Shinden Ryu and Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu and there is even some

variation within the styles. Any detailed description of a kata

in this essay will be from MSR unless otherwise noted.

4. Thompson filled in the gaps by referring to the work of Anonymous

Highland Officer (1790), Mathewson (1805), and McBane (1728).

Original source material in scholarly journals is generally preferred,

but having read Anonymous Highland Officer, Thompson’s conclusions

sound logical. Furthermore, Thompson's book has been favorably

received by the Western martial arts community. Therefore as a

novice in the Western fencing tradition I have referred to his

explanations when the meaning of the original poster is unclear.

5. Dr. Friday, Menkyo Kaiden (license of full transmission), Kashima

Shin Ryu (a traditional school that has both weapons and empty hand

techniques), was speaking both about his areas of expertise and the

method of transmitting knowledge in his school. His books on

Japanese history and Kashima Shin Ryu are very enlightening and very

readable.

Bibliography

Amberger, J. C. (May 2005). Officers and Gentlemen: On The History Of

Fencing At The U.S. Naval Academy.

www.swordhistory.com/excepts/corbesier

Anonymous Highland Officer (1790). Anti-pugilism: the Science of

Defense Exemplified in Short and Easy Lessons for the Practice of the

Broad Sword and Single Stick. London: J Aitkin.

Angelo, H. and Rowlandson, T. (1799). The Manual of the Ten Division of

the Highland Broadsword. London: H. Angelo.

Angelo, H and Rowlandson, T. (1800). Hungarian and Highland

Broadsword. London: H. Angelo

Corbesier, A. J. (1869). Principles of Squad Instruction for the

Broadsword. Ohio: Navy and Marine Living History Association

Danzaki, T. (1988). Iaido Sono Riai to Shinzui. Tokyo: Taiku to

Supotsu Shupansha

Friday, K. (2003). Discussion on the transmission of kata after

Friday’s demonstration of kaiken (dagger) verses tachi (sword) kata

from Kashima Shin Ryu. Guelph Ontario.

Fullam, W. Lieut.Comdr. (1904). Petty Officer’s Drillbook.

Annapolis: Naval Institute

McGrath, J. and Barton, M. (2002). Naval Cutlass Exercise.

Portsmouth UK: Royal Navy Amateur Fencing Association.

Mitani, and Mitani (1986). Shokai Iai: Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu. Tokyo:

Tokyo Inshokan

Thompson, C. (2001). Lannaaireachd: Gaelic

Swordsmanship. United States: Ceilidh House.

Our

Sponsor, SDKsupplies